Before I get into this week’s blog, I want to give much credit to my good friend Mr. Don Smart. I’m sure his wife, Darlene (another awesome person in our historical-preservation crew), would agree with me that he goes above and beyond in his research and that he is constantly there if an organization needs a volunteer. Actually, both Don and Darlene are two treasures when it comes to preserving and teaching history!

Last week, during our Lincoln Rest Cemetery cleanup day, Don handed me a DVD of the Texas Historical Commission marker dedication at the World War II prisoner of war (POW) camp in China, Texas, that he filmed in 2000. A while back, he told me that he had footage of the dedication and the person I wanted to see. The person was Hans Keiling, a German tank commander who immigrated to Port Arthur. I posted his story back in 2022, and I will add it to this blog, but there was more information about his journey to Southeast Texas in the video. The footage also mentions letters written by relatives a some who were incarcerated at the China camp and even those who were young when the camp was established and who got to know the prisoners. This was a great video, and I thank Mr. Smart for always bringing these things to light; without his journey into history, a lot would be lost to time. For example, there would have been no video of the marker dedication. I will add that we also wouldn’t know the story of Wong Shu, who we believe is the person who lies under the Chinese stone on the tree line near the bayou at Magnolia Cemetery. It was Mr. Smart’s research on the Beaumont Enterprise that gave us Wong Shu’s story. I’ll leave a link at the bottom of this blog.

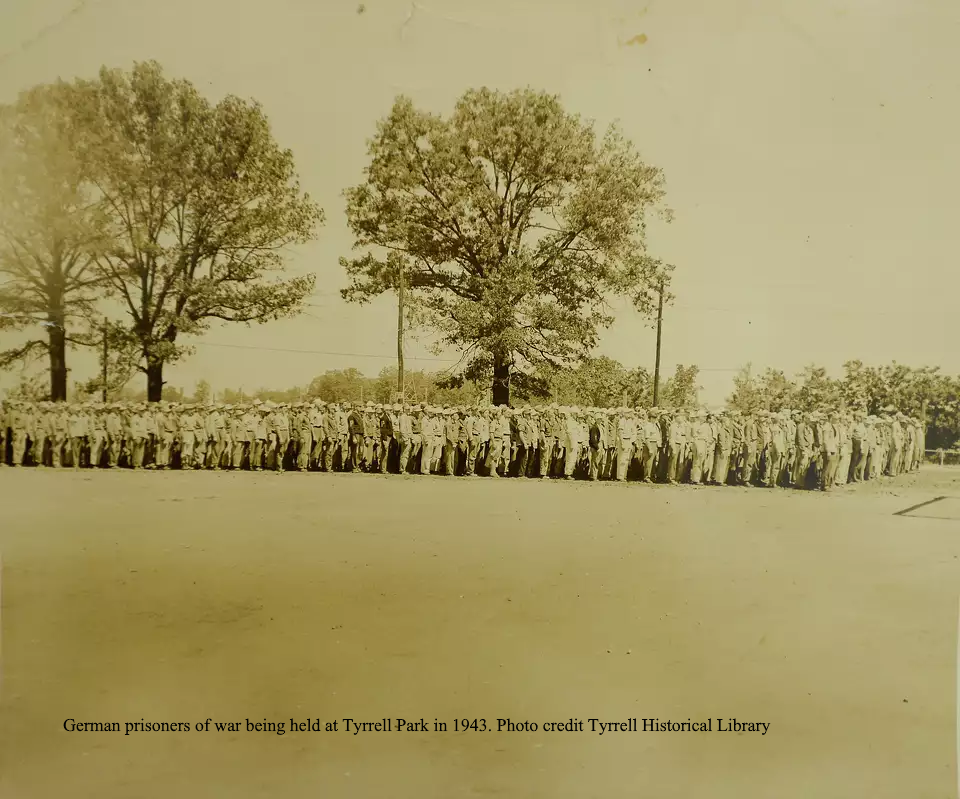

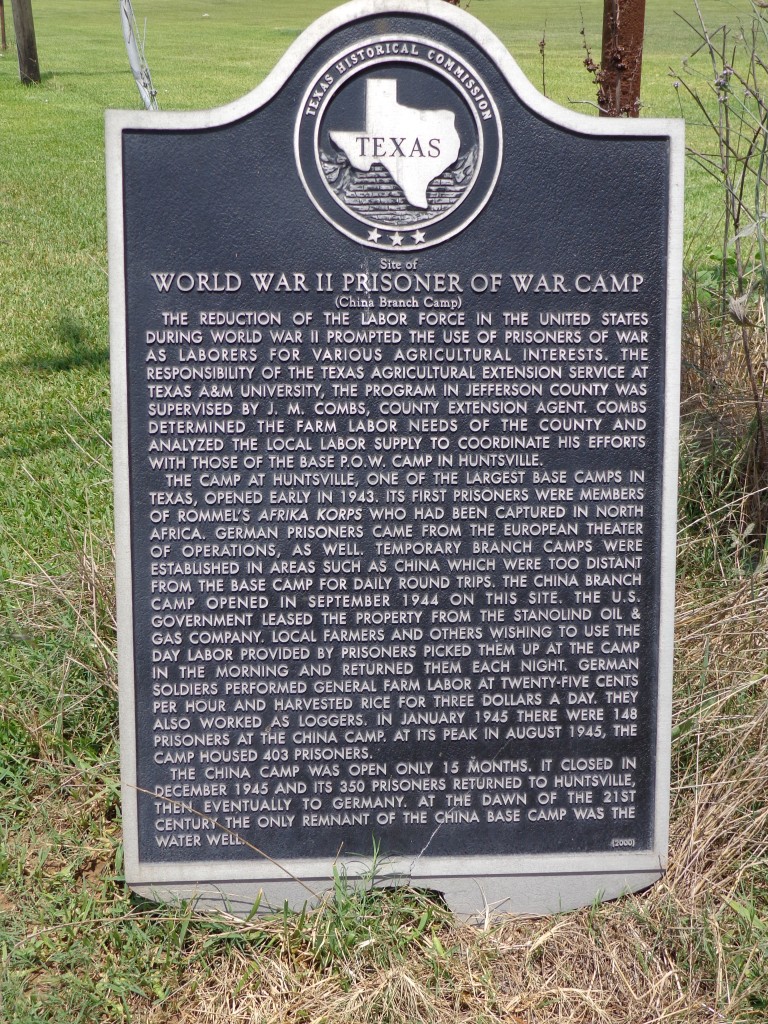

Getting back to Hans Keiling and the POW camp dedication, there were three camps in this area—one in Orange County, one in China, and one in Tyrrell Park in Beaumont.

By 1943, the war and its effects had been felt by people throughout the world. This was also true for our brave men and women here in Southeast Texas. Without hesitation, they answered the call of duty on three levels, doing their part in both the Pacific and European theaters as well as on the manufacturing front. Sacrifice and effort were given freely in support of the cause. Because of the need for wartime laborers, other sectors, such as timber and agriculture, suffered.

At the time, the number of German and Italian POWs was increasing, especially in North Africa. The surrender of 150,000 soldiers of General Rommel’s Afrika Korps resulted in their transfer to the United States where they remained incarcerated until the end of the war.

The Geneva Convention of 1929 required that POWs be located in a similar climate to that in which they were captured. This made Texas the ideal place for the Afrika Korps prisoners. At the time, Texas had twice as many POW camps than any other US state. In August 1943, there were 12 main camps, but by June 1944, there were 33. The need to house, feed, and care for these POWs was enormous, but Texas embraced the challenge.

In Southeast and East Texas, the arrival of (mostly German) POWs couldn’t have come at a better time. Smaller camps were erected throughout the region to aid timber and rice farmers. As I stated earlier, three sites—China, Tyrrell Park in Beaumont, and Orange County (off Womack Road)—housed prisoners who worked on the rice farms under the Texas Extension Service of the Texas Agriculture and Mechanical University.

During the camps’ existence, there were escape attempts. This was a significant problem for the sites near the Mexican border, but for the most part, the prisoners spent their time incarcerated without incident. And now for Mr. Keiling’s story.

Hans Max Keiling immigrated from Germany in 1956. His story should be a movie, as he is one of those immigrants who loved this country for its freedom.

Hans was from Frankfurt an der Oder, a German town on the Oder River, near the Polish border. He was drafted into the German army and became a master sergeant and a tank commander at 23. In a few newspaper articles, he stated he only fought the Russians (the Soviets) and never faced the Americans. From what I know of the Russian front, it was a logistic nightmare during which everyone waited for Der Failüre to see how many soldiers would die in order to hold at all costs some land they shouldn’t have taken in the first place. Keiling did his duty, but when the Germans surrendered, he didn’t want to surrender to the Soviet Army because he would have been executed. He stayed in an American camp for two days. However, he was turned over to the Soviets because of an agreement the Americans had with them to transfer prisoners who fought against either army. So, Keiling was handed to the Soviets, but without his uniform that showed he was an SS tank commander. He was put in a labor camp near Stalingrad, where he spent three and a half years working in a coal mine 14 hours a day.

In 1948, some of the POWs who had special training were sent to East Germany to train “police forces.” Keiling said he had to choose between staying in the coal mine, where he could perish any day, and going to East Germany. He chose the latter, signing an agreement under pressure from the KGB.

Keiling became a special-weapons training officer at the “police academy,” but he soon “found out that this training had nothing to do with police work.” Germany was secretly working to establish a new army, although prohibited from doing so under its terms of surrender.

Still, Keiling said he had no choice in the matter. One night in 1950, while walking to the post office, he was kidnapped by two KGB officers and was jailed for six months, during which he received monthly “hearings.” He was then sentenced to 10 years in a slave-labor camp. He was sent to a coal mine in Vorkuta, Siberia, 80 miles above the Arctic Circle. Each day, he marched three miles from the barracks to the coal mine, with the temperature usually around 45 degrees below zero. He was released when Stalin died in March 1953, but he remained in custody in the USSR. While being transported back to East Germany, he escaped to West Berlin.

In 1954, he settled in West Germany, where he met the niece of Bruno Shulz, the man who founded Gulfport Shipyard in Port Arthur. Keiling was finally able to emigrate from Germany in 1956. He moved to Texas and worked for Shulz, managing a trailer park he owned in Kerrville and working on his ranch in Comfort. It was in Texas that Keiling learned to speak English, in part from television. Keiling worked for Schulz until the latter’s death in 1981. Then, he moved to Port Arthur, where he worked as a security guard until 1984. Afterward, he moved to Temple and back to Port Arthur.

Hans passed in 2008, and he currently rests in Magnolia Cemetery in Beaumont, near fallen Beaumont police officer Paul Hulsey, who ended his watch in March 1988. This is another tale from that hallowed ground I may get into someday.

Until next week.

World War ll Prisoner of War Camp China:

World War ll Prisoner of War Camp Orange:

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=172281

World War II Prisoner of War Camp Beaumont:

https://secrethistoriesnow.blogspot.com/2016/12/tyrell-park-wwii-prisoner-of-war-camp.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.